What the Stone Remembers

The carved temples of Ellora Caves, quiet exchanges, and the many faces of India

Morning stillness: a woman sweeps in front of the cave temples at Ellora.

I was listening intently to the guide when I became aware of a slight shuffling motion beside me — a brief flash of green in my peripheral vision, then stillness. Although I didn’t glance over right away, I shifted my position slightly. Many of these historical sites are busy, and a small step aside is sometimes required when a group passes through. This spot, however, was mostly quiet, with only a few scattered tourists. I turned my attention back to the guide, but part of me stayed alert, tuned to that small disruption.

My travel companions and I were standing in Cave 32, one of the Jain caves at Ellora. This two-story structure had been carved directly into the basalt cliffs, and the room we were in, on the ground floor, appeared to be unfinished. In the dim light, I stood on the uneven stone, struck by the carved columns rising from the floor — plain and rectangular, emerging from shadow. Beyond them, the walls angled sharply, then softened into a ceiling that had been smoothed by hand. At one end of the room, I could see a small shrine and the faint outline of a figure inside. Our guide was explaining its significance, and though he spoke excellent English, I had to listen closely to follow his accented words.

The Ellora Caves are a series of over a hundred caves carved into the basalt cliffs of the Sahyadri Hills, about an hour northwest of Aurangabad, India, where we were staying. A UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983, thirty-four of the caves are open to visitors. Carved between 600 CE and 1000 CE, these elaborate structures are as layered and complex as the country itself, blending rock-cut architecture with a deep spirit of religious harmony. Filled with immense statues, columns, and faded murals honoring Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain iconography and history, these caves remain a living expression of coexistence. They served as monastic retreats and sanctuaries, but also as educational centers and stopover points for travelers.

The complex was used continuously until the 13th century, when it began to decline: a result of shifting political landscapes, invasions, and new dynasties that reduced patronage for religious upkeep. In the early 1800s, the caves regained attention as Indian and British historians began to document them, leading to conservation efforts in the following century under the Archaeological Survey of India. Today, they still serve in a limited religious capacity, though their primary role is as a site of cultural tourism.

Indra-Sabha , where we were standing, is in the section of Jain caves. One of the most elaborate and well-preserved, it is also a two-storied cave, one of only four in the complex. Walking through the entrance, we had entered a courtyard containing a smaller, free-standing rock-cut shrine, along with a carved elephant statue that dwarfed me in comparison. We continued up a short set of stairs into a large room carved into the stone; a welcome relief from the glare and heat outside. As our eyes adjusted, the guide paused. He explained that these caves had been carved without modern tools, requiring meticulous planning for a structure that would eventually be supported by the columns below. “Mistakes,” he said, “if they were made, could not be fixed.” His tone made the extraordinary nature of the work sink in. Shortly, we would climb the stairs to the upper room, which was far more elaborate in its carvings and murals.

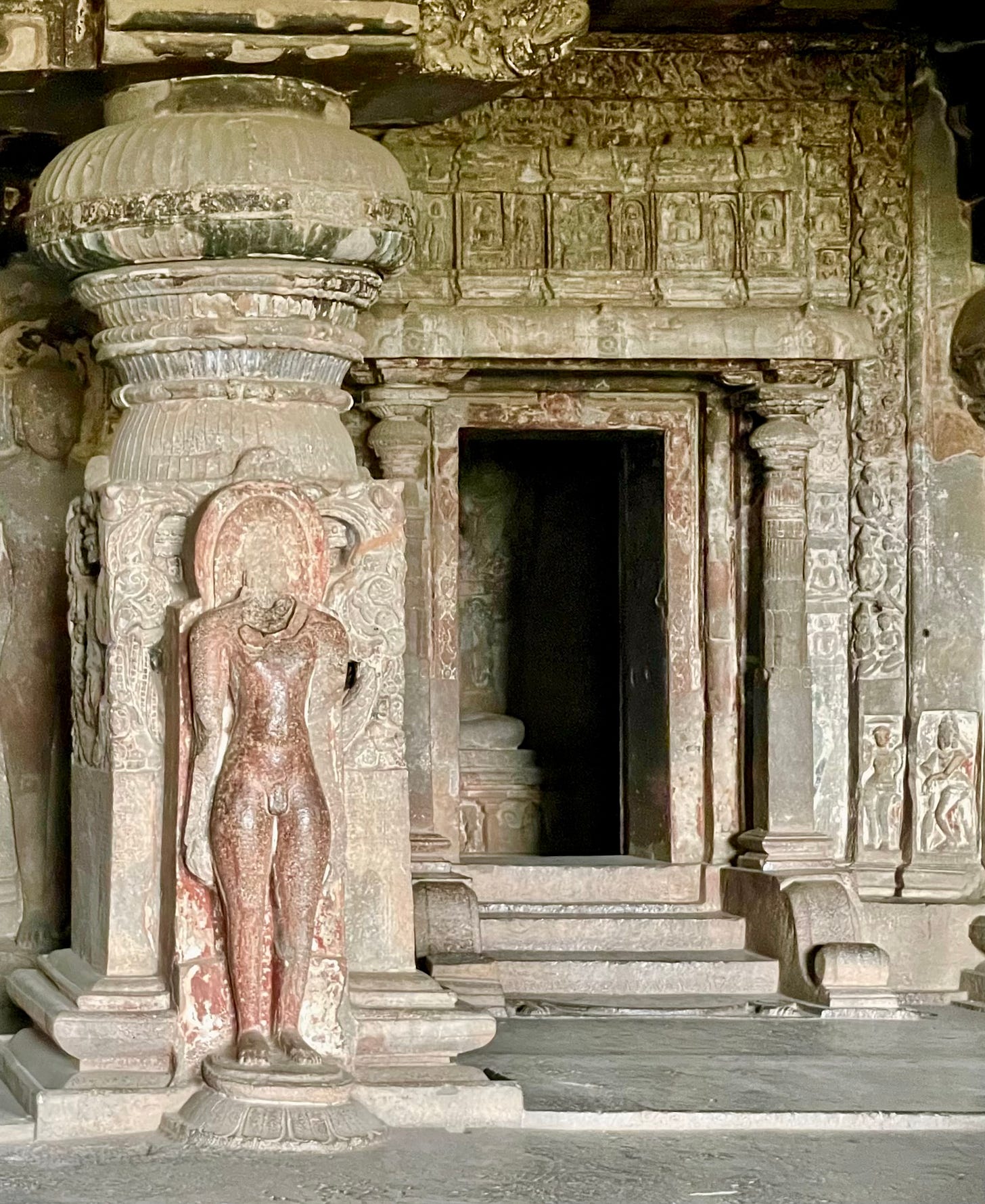

A quiet guardian in the shadows of the Jain caves.

It was there, among the stone columns, carefully planned and carved entirely from the rock itself, that I noticed it again. The flicker of green fabric. A whisper of color in a darkened world of grey stone.

The guide continued speaking, and I turned to look for the Jain tirthankara carvings he was describing. These tirthankaras, he explained, were the spiritual teachers who had attained liberation. As I moved to follow his words, scanning the room, I suddenly noticed a man standing a few feet away, next to one of the stone columns, moving his hand as if to motion someone.

“Closer,” the man seemed to be saying, with the directive, almost impatient motion of his hand. No words, just the universal language of gesture. Get closer. As I watched curiously, I realized he held a camera. Shifting my focus to see who he was addressing, the flash of green I had noticed earlier came into view: a woman in a green saree, following his request as she took a hesitant step in my direction.

I was startled. Me? Closer to me? The guide hadn’t noticed and continued speaking, but my attention was now fully on the woman near me. My surprise gave way to a smile and—although I didn’t know the Hindi word for “picture”—I made a small gesture to welcome her closer. She returned my smile and stepped beside me. Together, we stood, posing for her husband. Then I handed him my phone, because I, too, wanted a picture.

The thought that someone wanted a picture of me was a striking realization—how obviously different, as pale-faced foreign travelers, we were in this otherwise diverse country. But this wasn’t a one-way street. I was fascinated as well: by the faces of the people around me, the language, and the uniqueness of the clothing they wore. Women in beautiful sarees of intricate fabric, some woven with occasional golden threads that glistened as they caught the light. The men too—her husband included—stood barefoot, dressed handsomely in a beautifully patterned, blue-green, loose-fitting tunic called a kurta, worn over white trousers, or pajama, decorated at the hem with varied lines of colored thread.

By this time, the guide had left me behind, leading my travel companions up the narrow stone stairs to the second floor of this incredible structure. I bade the couple goodbye with a smile and a slight bow, my hands in prayer at my heart. I turned to follow after my companions, stepping carefully over the stone blocks in my path.

I had missed the explanation of the specific Jain tirthankaras, but the upper floor filled in some of my questions, even if I did not know their names. I found myself in an expansive, pillared room, the edges lined with elaborately carved stone columns.

Intricately carved columns in Cave 32, part of the Jain section at Ellora.

Varying in design, some columns featured celestial figures; others were carved as kalashas—large, sacred offering pots with wide bases and narrow necks—adorned with intricate floral designs and complex geometric patterns.

Along the side walls were carvings of previous tirthankaras, and although I still didn’t know their names, I understood that the largest shrine honored the 24th tirthankara, Mahavira. He sits in a lotus position in a shrine room, with carved Jain deities on the doorway, carefully guarding the entrance. Thought to have been born in the early 6th century BCE, Mahavira left his life of material wealth as a young man to seek spiritual realization. Upon finding it, he continued to teach until his death—teachings that would later be compiled by monks and become the foundation of the Jain religion.

After leaving the section of Jain caves behind, we proceeded to the Buddhist caves, starting with Cave 2, once a monastery. Fittingly, as we stepped into the darkened space, we were greeted by a solitary male voice rising in song. There was no music, no introduction — just his voice, strong and echoing through the stone. The room was narrow, the carved columns tightly spaced, and I couldn’t tell where he stood. The acoustics gave him a kind of omnipresence; his voice seemed to come from everywhere at once. I didn’t recognize the language or the melody, but it carried a haunting, meditative quality. Stunned into silence, we listened, held still by the weight of it.

When the song ended, our guide continued. We had now walked up the steps to the shrine at the end of the small monastic hall, which housed a colossal Buddha statue. Still in darkness, our guide used his flashlight to point out the key symbols of this particular portrayal, noting the broad head and square shoulders—features reflecting a transition from earlier traditions in which the Buddha was depicted mostly through symbols. Serving as a historical marker in time, these carvings would evolve again in later caves into richly detailed surroundings and more expressive features. Our guide pointed out the barely carved halo—visible only with his flashlight—and the flying angels near the Buddha’s head.

Buddha Statue in Cave 2, showing early design features.

We continued to Cave 6, which was expansive and open compared to the smaller cave we had just left. Featuring stark, square-carved columns topped with intricately carved circular capitals, they led to a large shrine room containing another seated Buddha statue, further illustrating the evolution of the iconography. This figure was now accompanied by attendants, bodhisattvas, and other celestial beings—including, for the first time on this journey, a carving of Tara, the protector, a revered female deity.

As we left, I noticed a monk in saffron robes outside, deep in concentration. He wasn’t leaning against anything but instead balanced carefully on the uneven rock of the portico, reading a small book in his hands. It was so small that, at first, I thought he was holding a cell phone.

We walked carefully across the stone pathways, making our way to Cave 10. Upon entering, I immediately felt as if I were in an ancient, sacred temple. Twelve columns flanked a narrow central hall that led to a carved arch and a seated Buddha statue. But what was most astounding was the ceiling. Horseshoe-shaped, it had been carved to resemble wooden beams, hence the name “Carpenter’s Cave.” This unique formation also allowed more light to filter in, and as it illuminated the ceiling, the shadows accented the grooves, giving it an otherworldly, hallowed feeling.

Cave 10, known as the Carpenter’s Cave, with its vaulted ceiling and serene Buddha figure.

A group of boys had gathered near the statue and were just turning to leave when they noticed me. Without hesitation, one of them approached, holding up his phone and gesturing—he wanted a picture with me. I smiled. Of course.

They were kind, grinning shyly as we took photos together. There were six in total, and each one, practicing their English, asked my name and told me theirs in return. Some even ventured to ask how I was, and I answered, choosing my words carefully so they’d be easy to understand. A couple of the boys hung back at first, more hesitant than the others. I couldn’t understand their language, but I could appreciate the moment; the gentle nudges, the low words of encouragement from the braver ones. Get up there. Stand next to her—it’s fine. Come on. The urging that needs no translation.

In the end, they each shook my hand, said thank you, and we stood together for a group picture. And then, just like that, they were gone.

How many times have I had the courage to ask a stranger for a photo? Once, maybe. I couldn’t help but admire their confidence and willingness to step beyond comfort for a moment of connection. Smiling to myself, I couldn’t help but wonder if I would end up on Instagram.

As we exited the cave, the heat of the day was beginning to make itself known. Although still morning, the temperature was approaching 90 degrees as we started our walk to the final cave we were to visit: Kailasanatha Temple.

Also known as the Kailasa Temple—a name that references Mount Kailasa, the mythic abode of Shiva—it is the crown jewel of the Ellora Cave Complex. Carved from a single rock, it stretches 276 feet in length and 154 feet in width, a monolithic marvel larger than a football field. Commissioned in the 8th century by King Krishna I of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, the temple’s formal name, Kailasanatha, means “Lord of Kailasa”—a direct reference to Shiva, to whom the temple is devoted.

We approached the temple not by climbing up to it, but by descending into it. The entrance led us through the rock wall, giving the uncanny sense of entering the mountain itself. A moment later, stepping into the courtyard, I was startled to find such massive yet intricately detailed structures—not built but carved. Overwhelming and complete, it was impossible to take it all in at once.

The scale of the Kailasanatha Temple unfolds inside a vast sunken courtyard.

Carved from the top down, removing the rock as they went, this single block had been transformed into sculptures, shrines, staircases, and corridors everywhere I looked.

Two massive columns, each fifty-six feet high, known as dhvaja stambhas, Sanskrit for “flagstaff pillars”, greeted us as we entered. They flanked the entrance to the Nandi Pavilion, named for Shiva’s sacred bull and devoted companion, Nandi. The pavilion itself was carved from a single piece of stone. From top to bottom, the pillars were covered in intricate details: garlands, lotus motifs, and figures that appeared to be Hindu deities.

Walking us around the columns, our guide stopped just outside the Nandi Pavilion, offering a final explanation in the shade. He declined to come in with us. The temple’s inner sanctum, he said, was best experienced on our own, quietly and with reverence. And so, we stepped inside, into the cool dimness, where the carved stone seemed to breathe around us.

After a moment or two, walking carefully, we arrive at the Shiva lingam; present but untouched. The lingam, or linga, is the primary symbol of Lord Shiva in Hindu worship, its abstract vertical form represents the mountain of Kailasa itself. In active temples, this symbolic sculpture would be overflowing with offerings; however, in this heritage site, its purpose is quiet preservation and contemplation.

The interior sanctum of the Kailasanatha Temple.

For me, the main temple itself could take an hour or more, but time is limited. Back outside we go, to walk with our guide around the complex itself, learning about the multiple carved towering panels. Lifesize images of goddesses, elephants carved along the lower story, appearing to support the structure. A large, intricately carved panel details Ravana, the demon king, shaking Mt Kailasa, Shiva’s home. Walking around, I realize that I am not even as tall as the stepped base that the elephants are carved upon.

We were in the process of leaving when I looked back and noticed them.

Two women resting on the temple steps — a moment of stillness in the afternoon heat.

On the wide steps leading up to the pillars, two women sit, taking a break from the heat. I raise my phone, instinctively hoping to capture the scene—but I pause, remembering the couple and the boys I had met earlier. Instead of taking the photo, I climb the steps and approach them, trying to communicate my request. With no shared language, I show them my phone, miming the gesture. They smile and nod, a quiet welcome, kind and clear.

I return to my spot below, pause, and take the picture — a quiet exchange, brief but generous, before moving on to explore more of this country and the people who continue to welcome us in. In that moment, their welcome felt mutual — like the boys’ laughter and the couple’s smile earlier that morning. Each encounter, quiet and generous, as if they wanted to remember us as much as I hoped to remember them.